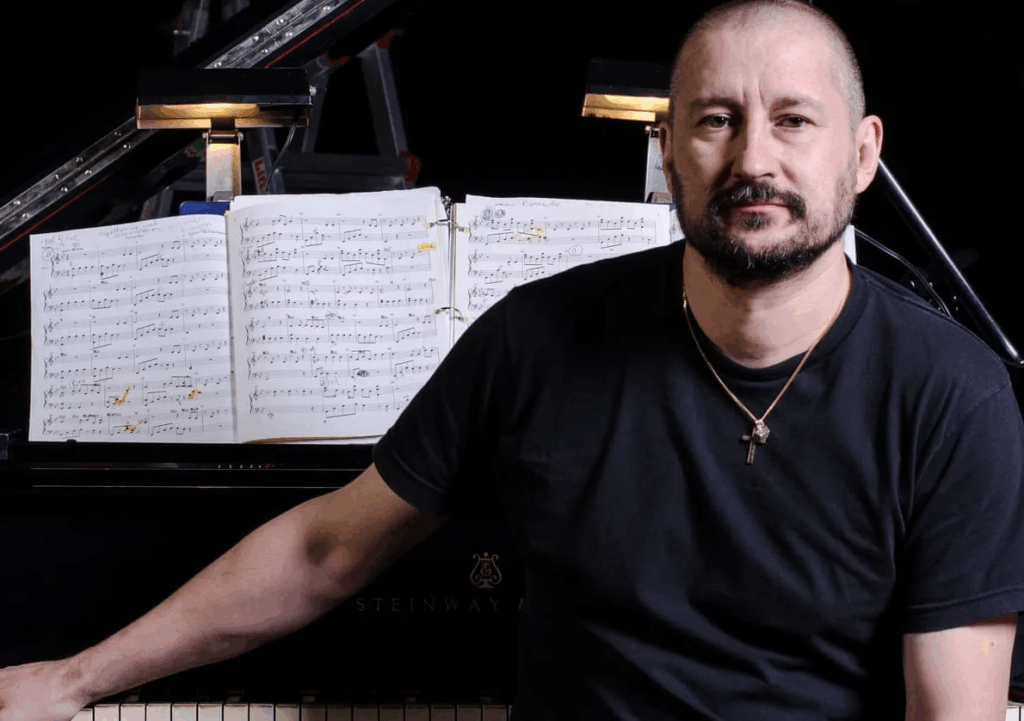

Clint Mansell

The Sound of the Soul

Charting the Emotive, Unorthodox Genius of Clint Mansell

In the vast, often formulaic landscape of cinematic sound, a film score can serve many functions. Too often, it is mere sonic wallpaper, a functional but forgettable layer designed to cue emotions without leaving a lasting impression. Then there are the scores that become as integral to a film’s identity as its cinematography or its lead performance—scores that don’t just accompany the narrative but inhabit its very soul. It is in this rarefied space that the work of Clint Mansell resides. A composer whose journey began not in a conservatory but in the anarchic, sample-heavy world of British alternative rock, Mansell has forged a career built on a singular, unmistakable voice. His music is a conduit for the psychological and emotional undercurrents of a story, often favoring minimalist dread over orchestral bombast and raw, instinctual feeling over technical flourish.

When Mansell first met director Darren Aronofsky, they bonded over a shared disdain for the state of contemporary film music, which they dismissed as “fucking wallpaper”. This rebellious sentiment, born from a punk-rock ethos, would become the foundational principle of one of modern cinema’s most fruitful collaborations. Mansell’s approach is that of a “method composer,” one who immerses himself in a project’s thematic and psychological world to find its unique sound. He is not merely writing music; he is a sonic psychologist, translating the complex inner lives of characters into haunting, emotive soundscapes. This process has produced some of the most iconic and culturally resonant musical pieces of the 21st century, none more so than “Lux Aeterna” from

Requiem for a Dream, a composition so powerful it transcended its harrowing origins to become the default soundtrack for epic drama itself.

His career represents a powerful testament to the idea that a composer’s true strength lies not in formal training, but in an authentic, inimitable voice. His outsider status is not a footnote to his success but the very source of it. By rejecting convention and trusting his gut, Mansell has crafted a body of work that is challenging, deeply personal, and utterly unforgettable, proving that the most profound music often comes from the most unorthodox of places.

From PWEI to Pi – The Grebo Origins of a Film Composer

Before Clint Mansell became the architect of some of cinema’s most haunting soundscapes, he was the frontman for Pop Will Eat Itself (PWEI), a band that was a chaotic, brilliant product of the UK’s late-80s “grebo” scene. Born in Coventry, England, Mansell’s musical education was not one of classical theory but of punk-rock revelation; he cites seeing David Bowie on Top of the Pops and hearing the Ramones as life-changing moments. This foundation in raw, three-chord energy evolved as PWEI did. The band began as a Buzzcocks-influenced indie outfit before being introduced to computer-based music and sampling by producer Flood. They quickly morphed into pioneers of a new sound, a fusion of punk, industrial rock, hip-hop, and electronic dance music that was as irreverent as it was innovative.

PWEI’s music was a collage of appropriated sounds, a testament to the art of deconstruction and reassembly. This creative DNA—the sampling, the genre-mashing, the do-it-yourself ethos—was the perfect, albeit unintentional, training ground for a future film composer. The band’s journey eventually led them to sign with Nothing Records, the label owned by Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails, a longtime fan of their work. After PWEI disbanded in 1996, Mansell moved to the United States, hoping to launch a solo career. He found himself creatively adrift until Reznor extended a lifeline, offering him an apartment in New Orleans and introducing him to the digital audio workstation Pro Tools. This mentorship was crucial, providing Mansell with both the space and the tools to transition from rock frontman to composer.

It was during this period that a mutual friend introduced him to a young, unknown filmmaker named Darren Aronofsky. Aronofsky, who was unaware of Mansell’s PWEI past, connected with him over a shared love for hip-hop and a mutual belief that most film music was terrible. Aronofsky initially only wanted an opening title piece for his micro-budget debut,

Pi, as he planned to use pre-existing electronic music for the rest of the film. However, when a lack of funds made licensing established tracks impossible, he hired Mansell to score the entire movie. The resulting score—a raw, pulsating electronic work born of necessity—earned Mansell his first award and launched one of cinema’s most important artistic partnerships. The film itself, made for a mere $134,815, became an indie phenomenon, grossing over $3.2 million and announcing both men as formidable new talents.

Looking back, it’s clear that Mansell never truly left his rock-and-roll roots behind; he simply found a new medium. His compositional process mirrors that of a band in a studio: he constructs his scores from foundational rock elements—drums, bass, guitar, and vocal lines—before an orchestrator helps flesh them out. He treats classical music not as a sacred text but as a source to be sampled and remixed, most famously in

Black Swan. His scores are not collections of disparate cues but cohesive, album-like experiences, designed to be listened to as a whole. In essence, he never stopped being a musician in a band; the film itself just became his new lead singer.

The Aronofsky Alliance – A Director-Composer Symbiosis

The partnership between Darren Aronofsky and Clint Mansell stands as one of the most symbiotic and defining director-composer relationships in modern film. It is a collaboration built not just on professional respect, but on a shared artistic frequency. Both are drawn to stories of obsession, psychological decay, and the harrowing, often brutal, search for transcendence. Their work together is a testament to what can be achieved when sound and image are not merely paired, but are born from the same creative impulse.

Their alliance was forged in a shared philosophy, a mutual rejection of the cinematic status quo, and a love for the atmospheric, minimalist scores of directors like John Carpenter. This foundation allowed for an unusually intimate and integrated creative process. Unlike most composers who are brought in during post-production, Mansell is often involved from the very beginning, absorbing ideas and developing musical concepts even before a single frame is shot. This early involvement allows the music to grow organically with the film, becoming an intrinsic part of its narrative fabric rather than an afterthought.

Across their six collaborations, this dynamic has produced a body of work that is as varied as it is thematically consistent:

- Pi (1998): A raw, gritty score born from budget constraints, its lo-fi electronic sound perfectly mirrored the protagonist’s fractured, mathematical obsession.

- Requiem for a Dream (2000): Their breakout masterpiece, a film and score that plunged audiences into the visceral horror of addiction, establishing their signature aesthetic of beautiful suffering.

- The Fountain (2006): An ambitious, sprawling, and divisive epic. The score, years in the making, evolved dramatically as the film’s scale shifted, resulting in their most polarizing and, for many, most profound work.

- The Wrestler (2008): A stark departure, this score was stripped-down and raw, relying on haunting, ambient guitar to capture the quiet desperation of its aging protagonist.

- Black Swan (2010): An audacious act of musical deconstruction, where Mansell warped and shattered Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake to score a descent into madness.

- Noah (2014): Their take on the biblical epic, imbued with a dark, modern sensibility that subverted genre expectations.

What makes this partnership so potent is that Mansell’s music functions as a character’s internal monologue. Aronofsky’s films are intense psychological portraits, and Mansell’s scores are the sound of those psyches. In Requiem for a Dream, the iconic theme “Lux Aeterna” is not just background music; it is the “monster theme,” the sound of the addiction itself claiming a victory. In

Black Swan, the splintering and distortion of Tchaikovsky’s classic ballet directly mirrors Nina Sayers’s mental and physical transformation; the score is her fracturing identity. Mansell provides the non-verbal narrative, the emotional subtext that dialogue and even performance cannot fully articulate. In this way, his role transcends that of a traditional composer, becoming something closer to a co-author of the film’s deepest, most unsettling truths.

Deconstructing the Masterpieces – Deep Dives into Key Scores

While the Aronofsky alliance forms the spine of his career, Mansell’s body of work is rich with iconic scores that have left an indelible mark on cinema. Analyzing his most significant compositions reveals a composer of incredible range and emotional depth, capable of crafting sound worlds that are by turns terrifying, heartbreaking, and transcendent.

Requiem for a Dream (2000): The Birth of a Cultural Phenomenon

If Pi was the opening statement, Requiem for a Dream was the thunderous declaration that a major new voice had arrived. The score is a masterclass in minimalist dread, a sonic representation of addiction itself. For the project, Mansell collaborated with the world-renowned

Kronos Quartet, a decision that proved transformative. The quartet’s visceral, human performance of the string arrangements, layered over Mansell’s electronic beats and textures, grounds the score in a raw, inescapable pain. The music is structured in three movements—Summer, Fall, and Winter—mirroring the characters’ seasonal descent from hopeful ambition to devastating ruin.

The centerpiece of the score, “Lux Aeterna (Requiem for a Dream)” is built on a deceptively simple, haunting chord progression that becomes, as Mansell describes it, an “addictive uroboros of despair”. Within the film, it functions as the “monster theme,” its every appearance signaling another victory for the characters’ all-consuming addictions. The score was met with universal acclaim from critics and audiences, who found it powerful and perfectly attuned to the film’s devastating tone.

However, the score’s true, and perhaps most complicated, legacy was born when “Lux Aeterna” was re-orchestrated with a full orchestra and choir for the trailer of The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. This new version, titled “Requiem for a Tower,” became a cultural phenomenon, single-handedly defining the sound of “epic drama” for a generation of moviegoers. Its use became ubiquitous, a go-to musical cue for countless trailers, television shows, and sporting events seeking to evoke a sense of high stakes and intensity. This widespread appropriation created a fascinating paradox: a piece of music conceived to articulate the bleak, internal horror of drug addiction was stripped of its context and commodified to sell blockbuster entertainment. The emotional core of the composition was hollowed out, leaving only its sonic shell to be used as a shorthand for “epic.” It is a powerful testament to the unforgettable nature of Mansell’s melody, but also a cautionary tale about how easily profound artistic statements can be diluted by the machinery of mass media.

The Fountain (2006): A Divisive, Hypnotic Odyssey

Perhaps no project better encapsulates the ambition and artistic purity of the Aronofsky-Mansell collaboration than The Fountain. A sprawling, philosophical film about love, death, and reincarnation, it demanded a score of equal scope and complexity. Mansell spent years developing the music, which evolved significantly as the film itself changed from a large-scale epic to a more intimate story. The final score is a monumental work, a collaboration with both the

Kronos Quartet and Scottish post-rock band Mogwai. It is built on minimalist, cyclical motifs that weave through the film’s three timelines, blending plaintive piano, ambient drones, and Mogwai’s signature swells of guitar noise into a cohesive, hypnotic whole. The score culminates in the staggering, nine-minute track “Death Is the Road to Awe,” a piece that encapsulates the film’s entire emotional and spiritual journey.

Upon release, both the film and its score proved to be deeply polarizing. While the film was a commercial failure, grossing only around $16 million on a $35 million budget, its score developed a passionate cult following. Fans on forums like Reddit hail it as a “masterpiece” and “hauntingly beautiful,” often citing it as Mansell’s greatest achievement. Conversely, some professional critics found the score to be “cold and clinical,” its repetitive nature “annoyingly persistent” and “one-dimensional”.

This stark divide between audience adoration and critical dismissal highlights a fundamental schism in how film music is often evaluated. Critics, particularly those judging from a traditional musicological perspective, faulted the score for its perceived lack of harmonic complexity and thematic development, viewing its minimalism and repetition as flaws. For them, it failed to meet the standards of intellectual and technical sophistication. Audiences, however, connected with the score on a purely visceral level. For them, the repetition was not a bug but a feature—a hypnotic, meditative quality that induced an emotional state perfectly in tune with the film’s philosophical themes. The score’s success with listeners proves that emotional immersion can be a more powerful metric than technical complexity.

The Fountain challenges the very definition of a “good” score, demonstrating that the most effective music is not always the most intricate, but the music that best serves the soul of the film.

Moon (2009): The Sound of Loneliness

For Duncan Jones’s brilliant and heartbreaking sci-fi debut, Moon, Mansell delivered a score that is the sonic embodiment of isolation. Stripping his sound down to a sparse, minimalist palette of piano, synths, and strings, he crafted a soundscape that is both intimate and vast, perfectly capturing the loneliness of a man stranded in the silence of space. The score is built around a simple, repeating two-note piano refrain that serves as the film’s central motif. This hypnotic, circuitous melody reflects the protagonist Sam Bell’s repetitive daily existence, his flickering memories, and ultimately, his fracturing identity.

The music in Moon is a journey of pure mood. It moves from the enchanting, atmospheric piano of “Welcome to Lunar Industries” to moments of blissful, ambient space-rock, mirroring Sam’s emotional trajectory from quiet resignation to dawning horror and defiant hope. The score was widely praised by critics and fans alike for its subtlety and emotional depth, earning Mansell a British Independent Film Award for Best Technical Achievement. The film itself was a critical and modest commercial success, earning over $10 million on a $5 million budget and cementing Jones as a major new talent.

The score for Moon represents the purest distillation of the “Mansell Method.” It is a powerful counter-narrative to the idea that his sound is defined solely by the epic bombast of “Requiem for a Tower.” Here, he demonstrates that emotional profundity can be achieved with the sparest of elements. By using minimalist, repetitive structures rooted in his rock and electronic sensibilities, he builds a psychological landscape that is deeply moving and unforgettable. It is a masterpiece of understatement, proving that sometimes the quietest sounds speak the loudest.

Black Swan (2010): Shattering a Classic

With Black Swan, Mansell undertook his most audacious project yet: the deconstruction of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s iconic ballet, Swan Lake. Approaching the revered classic with what he termed a “punk rock attitude,” Mansell didn’t just adapt the music; he shattered it, remixed it, and rebuilt it into a terrifying reflection of protagonist Nina Sayers’s psychological collapse. The score becomes a battleground where the elegance of Tchaikovsky’s original compositions is besieged by Mansell’s arsenal of groaning electronics, atonal shrieks, and industrial noise.

This musical schizophrenia is the score’s central triumph. As Nina’s grip on reality loosens, so too does the integrity of Tchaikovsky’s music. Beautiful, familiar melodies are warped and degraded, interrupted by jarring sounds and unsettling textures that crawl under the listener’s skin. The score is a direct sonic parallel to Nina’s horrifying transformation, with the music itself becoming a character in her psychodrama. The film was a massive critical and commercial success, grossing an astounding $329 million on a $13 million budget and earning Natalie Portman an Academy Award for Best Actress. Mansell’s score was nominated for a Grammy, though it was controversially deemed ineligible for the Oscars due to its reliance on pre-existing material—a ruling that misunderstands the transformative nature of his work.

The score for Black Swan is the ultimate expression of Mansell’s artistic origins. His approach is not that of a classical adapter but of a producer in the rock and electronic tradition. He treats Tchaikovsky’s work not as a sacred text to be preserved, but as a sample to be manipulated, distorted, and re-contextualized. The entire score functions as a feature-length industrial remix, a musical collage that pits the 19th century against the 21st. It is the most explicit and brilliant fusion of his PWEI-honed sampling ethos and the world of orchestral film music, creating a hybrid that is terrifying, beautiful, and uniquely his own.

The Mansell Method – An Instinctive, Emotional Approach

Clint Mansell’s creative process is as unorthodox as his musical background. Lacking formal training, he is unburdened by the rigid rules of classical composition, a freedom that has allowed him to develop a method rooted in instinct, emotion, and deep collaboration. He approaches film scoring not as a technician but as an artist seeking a “voice” for the film. He describes it as a “gut” response, a fluid process of feeling what works rather than adhering to a strict theoretical framework. In his own words, the score already exists within the film; his job is simply to listen and “channel it”.

His method begins with immersion. He prefers to join a project early, absorbing the script, research, and visual ideas long before the final edit is locked. This allows him to filter everything he sees and hears through the lens of the film, letting inspiration strike from anywhere. He works from his own studio, crafting what he calls “shit demos”—raw, foundational ideas built from rock elements like piano, guitar, and programmed beats. He believes that if an idea has power in this stripped-down form, it will be transcendent when performed by world-class musicians. This highly collaborative process often involves sending stems and ideas back and forth with directors, allowing the score to evolve organically.

His musical influences are as eclectic as his sound, ranging from the minimalist repetitions of Philip Glass and the atmospheric scores of John Carpenter to the punk-rock fury of The Ramones and the art-rock genius of David Bowie. This diverse palette is the key to his signature hybrid sound, which seamlessly blends orchestral arrangements with electronic textures, industrial noise, and post-rock sensibilities.

Ultimately, Mansell’s creative process is one of profound empathy. He is a “method composer” not just in his dedication to research, but in his capacity for emotional transference. He doesn’t score the action on screen so much as he scores the internal, psychological state of the characters. For

Moon, his primary goal was “humanising and connecting with Sam,” to feel his pain and devastation. He has spoken openly about channeling his own experiences of grief and anxiety into his work, finding a personal, emotional entry point into the narrative. This is why his scores resonate so deeply and why he is famously selective about his projects. He must find a film that speaks to him, that “drags something out of him,” in order to create the magic that has come to define his career.

The Legacy of an Outsider

Clint Mansell’s journey from the pogoing frontman of a cult British rock band to one of Hollywood’s most respected and distinctive composers is more than just a remarkable career trajectory; it is a validation of the outsider’s path. By maintaining his authentic, unmistakable voice, he has carved out a unique space in the world of film music, proving that a non-traditional background can be a powerful asset. His legacy is not just in a collection of iconic themes, but in the way he has challenged and expanded the very definition of what a film score can be.

His work inspires a passionate, almost devotional, following. Online forums and fan discussions are filled with fervent praise for his scores, with listeners describing his music as “haunting,” a “masterpiece,” and an elemental force that elevates the films it accompanies. This popular adoration is matched by significant critical acclaim. Despite the polarizing nature of some of his more experimental work, he has been recognized with numerous awards and nominations, including nods from the Golden Globes and the Grammys, and wins at the World Soundtrack Awards and from various critics’ circles.

In recent years, Mansell has embraced his status, becoming more selective and prioritizing artistic independence over commercial output. He chooses to work with directors like Ben Wheatley, with whom he can forge the kind of deep, collaborative partnership that allows his best work to flourish. This commitment to artistry ensures that his voice remains undiluted.

Clint Mansell stands as one of the most vital composers of his generation. He has demonstrated that a score can be more than just accompaniment; it can be a film’s conscience, its nervous system, its broken heart. By infusing the cinematic soundscape with the raw emotion of punk rock, the hypnotic repetition of minimalism, and a profound understanding of the human condition, he has created a body of work that will endure for decades to come. He doesn’t just write music for films; he composes the sound of our deepest anxieties, our most profound sorrows, and our most desperate hopes.

| Film Title (Year) | Director | Worldwide Box Office (Budget) | Key Musical Collaborators/Elements | Critical/Audience Reception (Metascore/RT Score) | Key Awards/Nominations (for Score) |

| Pi (1998) | Darren Aronofsky | $4.7 million ($135k) | Electronic, Industrial, Lo-fi Synth | N/A / 87% (RT) | Birmingham Film Fest: City of Birmingham Award (Won) |

| Requiem for a Dream (2000) | Darren Aronofsky | $7.4 million ($4.5M) | Kronos Quartet, Hip-Hop Beats, “Lux Aeterna” | 68 (Metacritic) / 79% (RT) | OFCS Award: Best Original Score (Won) |

| The Fountain (2006) | Darren Aronofsky | $16.5 million ($35M) | Kronos Quartet, Mogwai, Minimalist Piano | 51 (Metacritic) / 52% (RT) | Golden Globe (Nominated), World Soundtrack Award (Won) |

| Moon (2009) | Duncan Jones | $10.7 million ($5M) | Minimalist Piano, Ambient Synth, Strings | 67 (Metacritic) / 90% (RT) | BIFA: Best Technical Achievement (Nominated) |

| Black Swan (2010) | Darren Aronofsky | $331.3 million ($13M) | Deconstructed Tchaikovsky, Orchestra, Electronics | 79 (Metacritic) / 85% (RT) | Grammy Award (Nominated), Chicago Film Critics (Won) |

| Stoker (2013) | Park Chan-wook | $12.1 million ($12M) | Piano, Strings, Percussion, Philip Glass | 58 (Metacritic) / 70% (RT) | N/A |

| High-Rise (2015) | Ben Wheatley | $4.1 million ($8M) | Orchestral, Woozy Atmosphere, 70s Retro | 65 (Metacritic) / 60% (RT) | Ivor Novello Award (Nominated) |